WRITTEN BY NAZRUL & TAMMY CHOWDHURY![]()

Austin’s Story

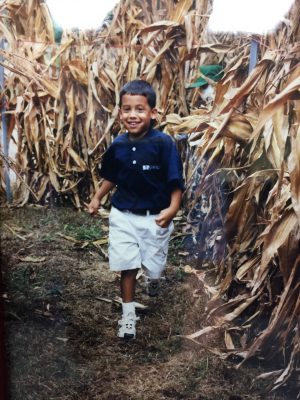

At the age of 24, opioids stole our son.

Austin was a wonderful young man. He was openhearted and generous, with a deep commitment to social justice and an optimism that saw the best in others. A great friend, he loved to travel, play basketball, and read. He embraced the world as he couldn’t know or experience enough.

On May 12, 2017, Austin Chowdhury received his Master’s in Urban Planning and beamed with his accomplishment. Perhaps he was so proud because he earned his degree while managing a full-blown addiction to heroin. Austin was a perfect example of a functional heroin user.

We learned he was using heroin on June 7th when he was arrested for possession after passing out behind the wheel of his car, as a reaction to drug withdrawal. The police found heroin in the car and the next day we went to court and spent the rest of the day together.

We learned he was using heroin on June 7th when he was arrested for possession after passing out behind the wheel of his car, as a reaction to drug withdrawal. The police found heroin in the car and the next day we went to court and spent the rest of the day together.

The next day we found Austin dead on his bedroom floor. How could this be? Just the night before he was talking and laughing as we watched a basketball game together.

The autopsy said his last dose of heroin was in fact a lethal mix of two drugs: Fentanyl and Cyclopropyl Fentanyl. Fentanyl is 100 times more potent than morphine and many times more potent than heroin. Later we learned a dealer brought his final dose the evening we watched basketball together.

We replay these events daily, thinking what-if. And we are left with doubt, guilt, and the never ending question: what could we have done to prevent his death?

Having just observed the first anniversary of Austin’s passing, we still think we let our son down because we didn’t understand the signs that screamed addiction. We were in denial, we were naïve, and we could not conceive he was using heroin.

From all of this, there are two things we want you to know:

First, addiction is a biological and chronic brain disease. People do not become addicted to opioids because of a character flaw, a lack of willpower, or a moral deficiency. They succumb to a powerful medication that changes their brain chemistry and causes physical and psychological dependence. Many are genetically predisposed to addiction.

Second, those with opioid addictions have disordered lives that are disconnected from their former routines. As their addictions deepen, they stop caring for themselves, they become estranged from friends and family, and they no longer take pleasure in pursuits that once brought order and joy to their lives.

Second, those with opioid addictions have disordered lives that are disconnected from their former routines. As their addictions deepen, they stop caring for themselves, they become estranged from friends and family, and they no longer take pleasure in pursuits that once brought order and joy to their lives.

After Austin passed away we found a notebook with his personal notes, including an entry about a session with a counselor at school. Apparently, she asked him to write down activities for a successful day. His answer was heartbreaking: eat three healthy meals, get enough sleep, shower, keep in touch with friends. We had no idea he had lost his bearings because, as we learned from his roommate, he would clean up when we visited.

And, in spite his difficulties, Austin called us every Sunday … to the end, he was unfailingly our kind, compassionate, loving, and a generous son.

Taking Action

Several months after Austin’s death, a friend introduced us to the Gaston Controlled Substances Coalition, a local organization that works to prevent opioid misuse and to help affected persons get treatment and support.

Gradually we became involved, committed to keeping Austin’s memory alive. Our mantra has been, “no one should experience our pain, no more parents losing their children to opioids”.

Our personal focus is to educate the community about opioids and remove the associated stigma.

Out of fear of criticism, many families silently live in pain about the addiction of their loved ones – be they in active addiction, early recovery, long-term recovery, or if they have died – and do not seek the professional and peer support that can help them find healing and peace.

Many fear others will say their loved ones don’t and didn’t have the willpower and moral strength to overcome opioids. They fear few will understand that opioid dependence often starts by following prescriptions, and that persons of all ages, races, incomes, and educational backgrounds are equally susceptible. They hear damaging words that say opioids is an issue of those people, not us. In truth, any of us could develop Opioid Use Disorder.

Many fear others will say their loved ones don’t and didn’t have the willpower and moral strength to overcome opioids. They fear few will understand that opioid dependence often starts by following prescriptions, and that persons of all ages, races, incomes, and educational backgrounds are equally susceptible. They hear damaging words that say opioids is an issue of those people, not us. In truth, any of us could develop Opioid Use Disorder.

Odds are strong that you, your friends or family, have loved ones who are addicted to opioids. If they tell you, treat them with kindness. Help them find a counselor, a NarAnon group, a supportive member of the clergy with whom they can speak. Help them to heal.

Invite a behavioral health or addiction specialist to speak to your employees. Add Narcan, the non-addictive medication that reverses opioid overdoses, to your first aid kits and train your staff to administer it.

Encourage your spiritual leaders to speak about opioids without stigma, and to embrace suffering congregants.

And, if you feel called to address opioids as a community issue, contact your health department to see if there is an opioid coalition in your county. The group will be thrilled for you to join them. Use your influence to make inroads with community leaders who are skeptical about the causes and effects of opioids. Help the coalition build its credibility, arrange community presentations, raise funds, and work with other business leaders.

Our family also established Austin’s Opioid Education Fund, at the Community Foundation of Gaston County, to support Coalition initiatives that mesh with our priorities.

FOR MORE INFORMATION

- Contact Nazrul with your questions.

- Watch the interview of Nazrul & Tammy on the Gaston Controlled Substances Coalition’s Facebook page.

- Learn more about opioids.

- Learn about the Community Foundation of Gaston County, which manages Austin’s Opioid Education Fund.

- Check out the Remembering Austin website.

- Help line: 1-888-235-(HOPE)4673

- Harm reduction: 828-291-7023